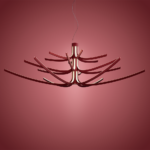

Dopo l’interpretazione del luminator che ha dato vita a Chiaroscura, Alberto e Francesco Meda tornano a reinterpretare un classico della luce per Foscarini, lo chandelier.

Dopo l’interpretazione della storica Luminator disegnata da Pietro Chiesa nel 1933, che ha dato vita a Chiaroscura, Alberto e Francesco Meda tornano a reinterpretare un classico della luce per Foscarini, lo chandelier. Lo fanno lavorando, ancora una volta, con estrusi di alluminio e integrando l’elemento luminoso all’interno del corpo stesso della lampada, concedendosi anche un divertissement decorativo ottenuto impeccabilmente grazie al gioco di incastri tra la fonte luminosa e il sostegno.

Perché, secondo voi, Foscarini vi ha chiesto di collaborare a questo progetto?

«Sicuramente Foscarini cercava una pluralità di mani e sguardi da impegnare sul tema della sperimentazione intorno al tema dello chandelier. Rispetto agli altri designer ingaggiati (Francesca Lanzavecchia e Dordoni Studio, ndr), la nostra forza penso sia insita nella ricerca di innovazione a partire dal dialogo tra materiali e tecnologie, interpretando in chiave contemporanea la tradizione senza stravolgerla nella sua essenza».

Da progettisti, qual era l’interesse in questo progetto?

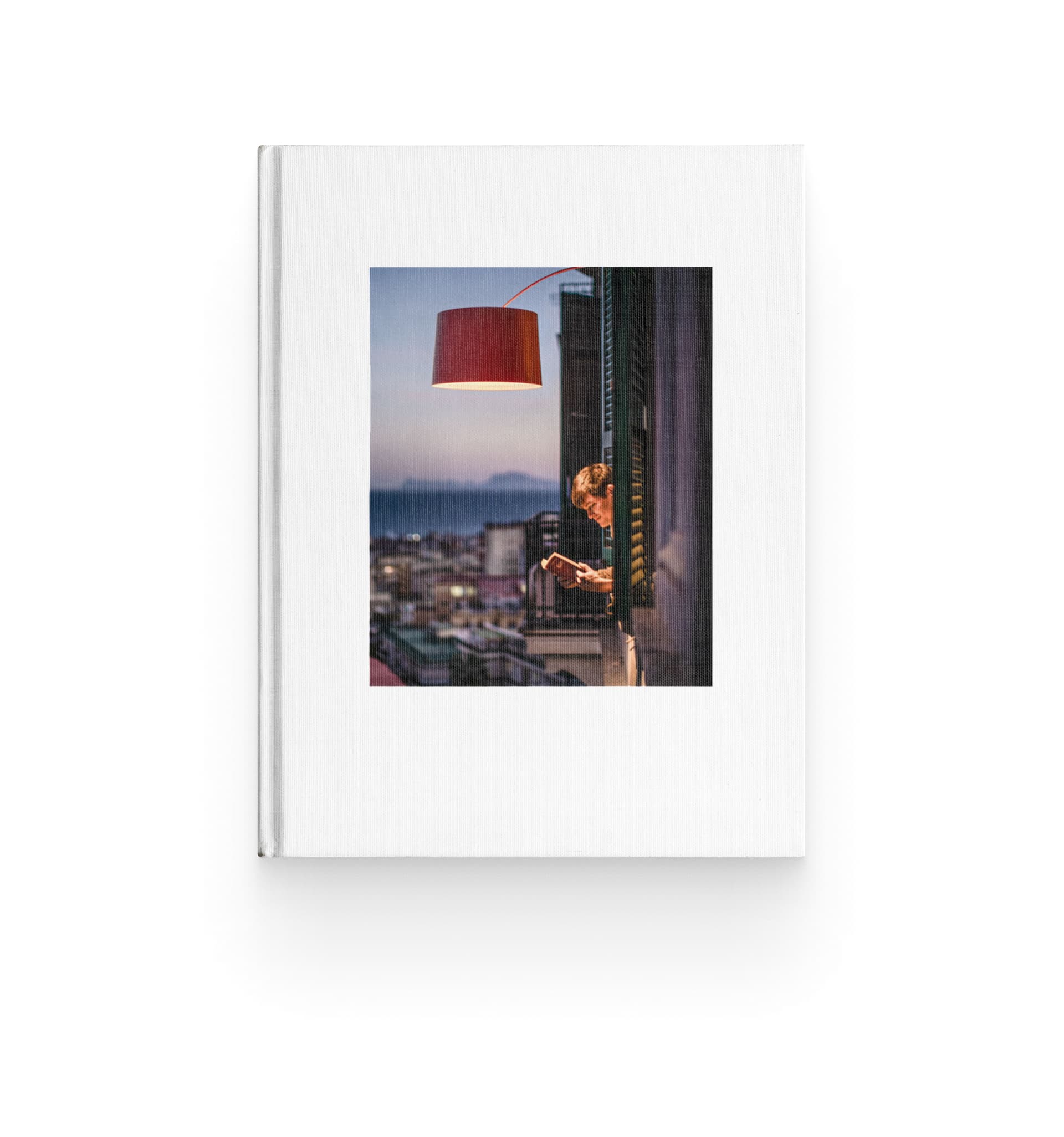

«Ci piace lavorare su tipologie rimaste immutate nel tempo. Lo abbiamo fatto con Chiaroscura, e lo stesso vale per lo chandelier, un oggetto studiato e reinterpretato infinite volte, ma sempre con un approccio basato sul decoro e sulla molteplicità delle fonti luminose. Noi, invece, abbiamo scelto di affrontare la sfida da una prospettiva opposta».

Quale?

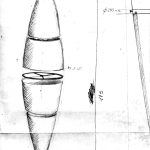

«Siamo partiti chiedendoci cioè dove ci avrebbe portati la tecnologia per l’illuminazione contemporanea, cioè i LED che offrono nuove opportunità che permettono di lavorare sulla qualità della luce e sulla sua distribuzione. Ci siamo chiesti, all’interno della tipologia del lampadario importante e centro stanza quale fosse la forma più essenziale che i LED permettevano di ottenere. Ne è uscita l’idea del braccio, con una striscia di LED, che è stato il punto di partenza del progetto».

Qual è la chiave di lettura per cogliere la portata innovativa di ASTERIA?

«La forza progettuale di ASTERIA sta nell’integrazione intima tra struttura e luce.

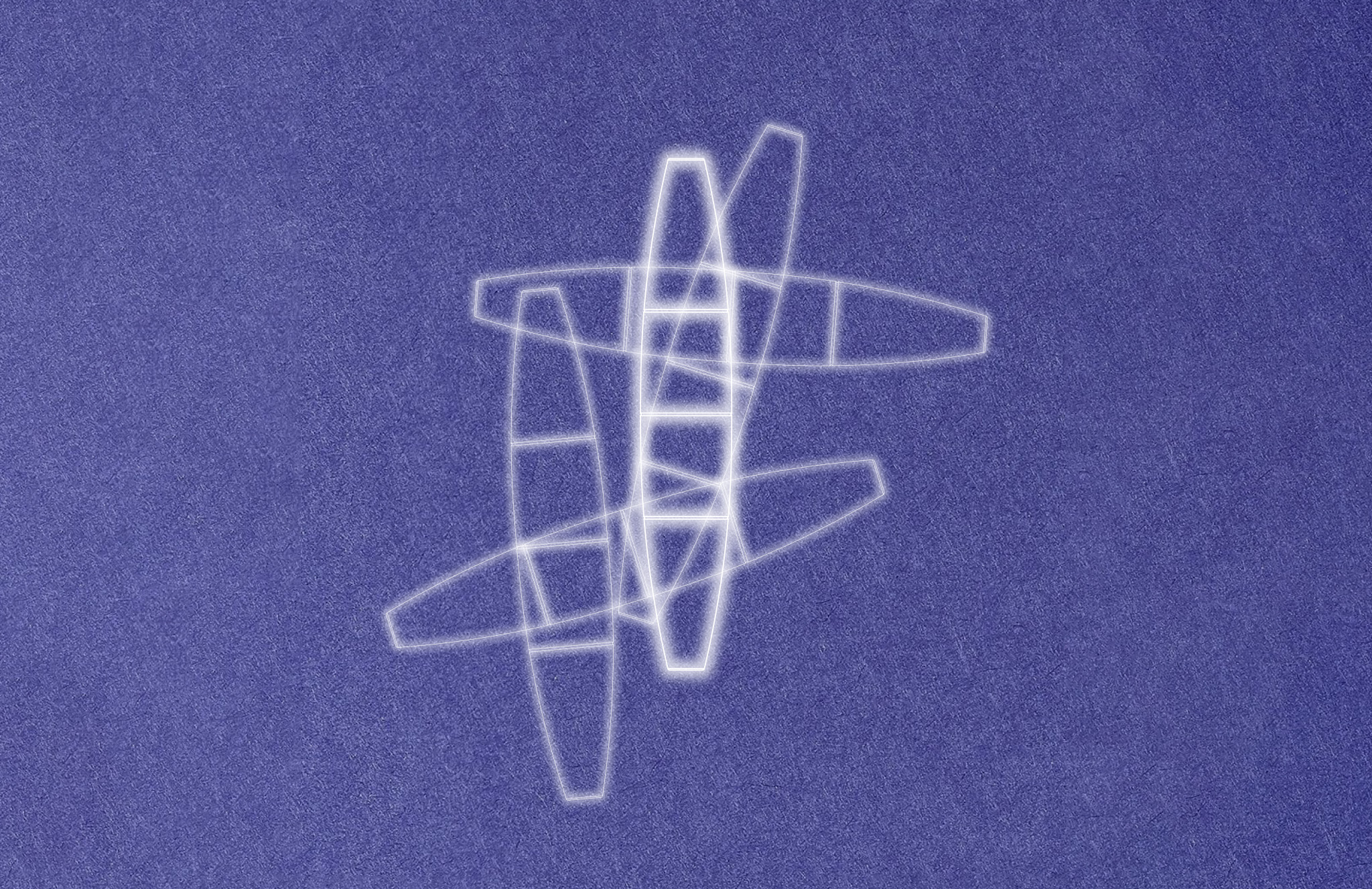

Come accennato, alla base del progetto c’è il braccio, un estruso di alluminio con una sezione a V, caratterizzato da un lato corto verticale e uno lungo che si estende orizzontalmente, curvandosi. La luce viene emessa da una striscia LED incassata nella parte superiore del braccio e coperta da una pellicola trasparente, che straborda in modo impercettibile sui lati e permette alla luce di fuoriuscire leggermente. Questo dettaglio rende la fonte luminosa percepibile anche a chi osserva il braccio dal basso o lateralmente.

Il braccio, che funge sia da struttura che da diffusore, è collegato a un cilindro centrale verticale. Sei braccia formano un livello dello chandelier, con un massimo di tre livelli sovrapposti in modo sfasato.

Quando acceso, ASTERIA emette luce in più direzioni: verso l’alto, in modo radiale grazie alla sovrapposizione dei livelli, e con una sottile linea luminosa quasi grafica dove il LED fuoriesce leggermente da ogni singolo braccio. Inoltre, se posizionato sopra un tavolo, fornisce anche luce diretta, grazie a un’ulteriore fonte luminosa posta nella parte inferiore del cilindro centrale».

Raccontato così sembra un lampadario modulare. È così?

«Sì, ogni livello può esistere indipendentemente come lampada a sospensione. La modularità quindi c’è anche se, per mantenere una certa coerenza progettuale, le diverse configurazioni saranno proposte dall’azienda, nell’offerta di una certa varietà estetica e funzionale».

Come siete arrivati a una ridefinizione così essenziale del lampadario?

«Cercavamo un’evoluzione del concetto. Abbiamo lavorato sul braccio come elemento centrale, integrando la luce nella struttura. Inizialmente volevamo creare una struttura più rigida e lineare, ma ci siamo resi conto che risultava troppo fredda. Abbiamo quindi introdotto curvature e una disposizione più dinamica dei bracci per rendere il progetto più armonioso e contemporaneo».

Nello sviluppo del progetto, insieme a Foscarini, c’è stata un’evoluzione significativa rispetto al concept iniziale?

«Sì, soprattutto nell’idea di “spettinare” la composizione per evitare un’estetica troppo rigida. Questo è stato un contributo dell’azienda, che ha voluto dare maggiore dinamismo all’oggetto».

Come si capisce quando un progetto ha trovato il giusto equilibrio tra rigore e morbidezza?

«È un processo di affinamento continuo. All’inizio c’è sempre un rischio, ma man mano che si ricevono feedback dalla sperimentazione, si inizia a percepire se la soluzione funziona. Per questo l’affinità tra designer e azienda è così importante».

Cosa definisce la contemporaneità oggi?

«Vuol dire fare cose semplici – cioè risolte – dal punto di vista costruttivo e in cui le tecniche o le tecnologie che sono state utilizzate per ottenere quel risultato non sono esibite. Significa creare quindi oggetti meno connotati che, proprio per questo, possono durare di più nel tempo perché non soggetti alle mode».

Le mode però ci sono. È un problema?

«Sì, il rischio è un’omologazione eccessiva. Decenni fa l’elemento distintivo delle imprese italiane era la capacità di evolvere, mettere a punto pezzetti di conoscenza che poi altri ereditavano e portavano avanti. Oggi questa cosa è rarissima e la conseguenza è che quello che viene presentato alle fiere come novità è tutto molto uguale: quando qualcosa funziona commercialmente diventa subito un template da ripetere con o senza varianti. Lo stesso accade con i classici, riproposti all’infinito perché sono sicuri e commercialmente efficaci».

La mancanza di innovazione e il passatismo è un problema solo per gli appassionati di design?

«Noi pensiamo che diventerà un problema per le aziende. Soprattutto quelle piccole o giovani – che non hanno un heritage a cui attingere e copiano le forme e il flair dei classici invece di inventare qualcosa di personale e significativo. Quando il mercato sarà saturo, avranno un problema».

Alberto, hai detto che il design aggiunge un pezzo di conoscenza al preesistente. Come si fa a perseguire questo obiettivo?

«Bisogna essere curiosi degli sviluppi scientifici e tecnologici, senza cadere nella celebrazione della tecnologia fine a se stessa. Il design deve saper cogliere il valore innovativo della tecnologia e trasformarlo in un vantaggio funzionale ed estetico. Per esempio, tornando al tema dei classici rivisitati, è un esercizio che ha senso se si aggiunge al progetto originale quello che viene dalla ricerca in materiali più sostenibili, un settore in cui vedo che – effettivamente – molte aziende sono impegnate».

Cosa vedete nel futuro dell’illuminazione?

«Gli OLED potrebbero rappresentare una vera rivoluzione. Si tratta di sorgenti luminose puntiformi che, sebbene ancora relativamente costose, offrono grandi possibilità per i designer grazie alla loro capacità di emettere luce da una superficie piatta. Questa superficie può persino essere flessibile, simile a un tessuto, aprendo scenari inediti e variegati che meritano senza dubbio di essere esplorati».

Luce che non è solo funzione, ma presenza, carattere, espressione.