The sculpture-lamp Orbital became the first step in the relationship between Foscarini and Ferruccio Laviani, but it represented also a statement: with Orbital we got away from Murano blown glass for the first time, exploring a way of thinking that has now led to the use of over 20 different technologies.

Were you to narrate your relationship with Foscarini with an adjective, which one would you choose?

I’d choose two: it is a profitable and free collaboration. The first term sounds rather financial, but that is not its only meaning. The fact that almost all the lamps I have designed for Foscarini are still in production is obviously good news for my studio and for the company. But I call it profitable above all because having designed objects people still find appealing after 30 years is an enormous gain for a designer: it confirms that what you are doing has meaning. Then comes the theme of creative freedom. Foscarini has allowed me to move with extreme independence of expression from the product to spaces, without ever setting any limitations. That is truly something rare and precious.

In your view, how was it that you arrived at the expressive and creative freedom?

I think it is part of the way of being of the people involved. If a designer wins the company’s trust, Foscarini responds by leaving him total freedom of expression. They know that this is the way to get the best from the cooperation, for both parties. Obviously in the awareness that the work of instinct is then followed by the work of the mind. In my case, Orbital was the initial wager: would a lamp with such a particular aesthetic be a success? Would it stand up to the test of time? The response of the public was affirmative, and from that moment on our partnership has always been based on maximum freedom.

What does this liberty mean for a designer?

It gives you the possibility of probing different facets of the possible. For a person like me, who has never identified with one style or a particular type of taste, but periodically falls in love with avours, atmospheres and decorative aspects that are always different, this freedom is fundamental because it allows me to express myself. I do not have artistic pretences and I am well aware of the fact that what I do is for production: serial objects that have to have a clear function and perform it well. Alongside these rational considerations, however, what excites me in the creative act is desire. The almost irrepressible desire to bring about an object that did not exist: something I would like to have, as a part of my life.

What are these objects you desire, and therefore design, going to be like?

I don’t have an answer in terms of style: I always make different things because I always feel different, and I fill my physical and mental spaces with presences that vary in time and reect these personal landscapes. I am fascinated, however, by everything that creates a bond with people or between people. I always give a character to the things I design: the one that in my view best reects my way of interpreting the spirit of the time. Sometimes of the instant. This is much more true for a lamp, as opposed to a piece of furniture, because a decorative lamp is chosen for an affinity, for what it says to us and about us. It is the start of an ideal dialogue between designer and consumer. If the lamp continues to speak to people over time, even 30 years later, it means the conversation is relevant, and the lamp is still able to say something meaningful.

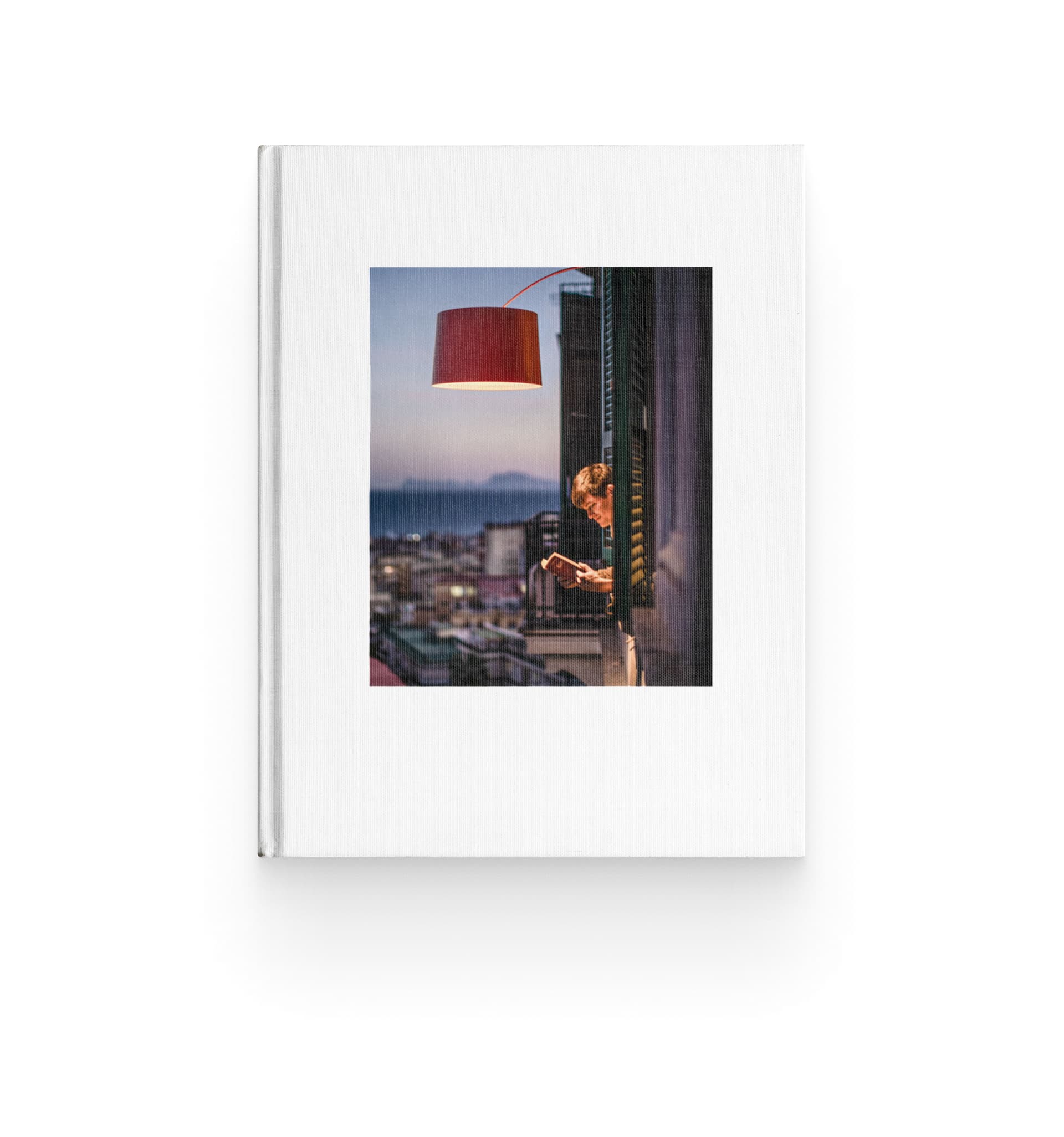

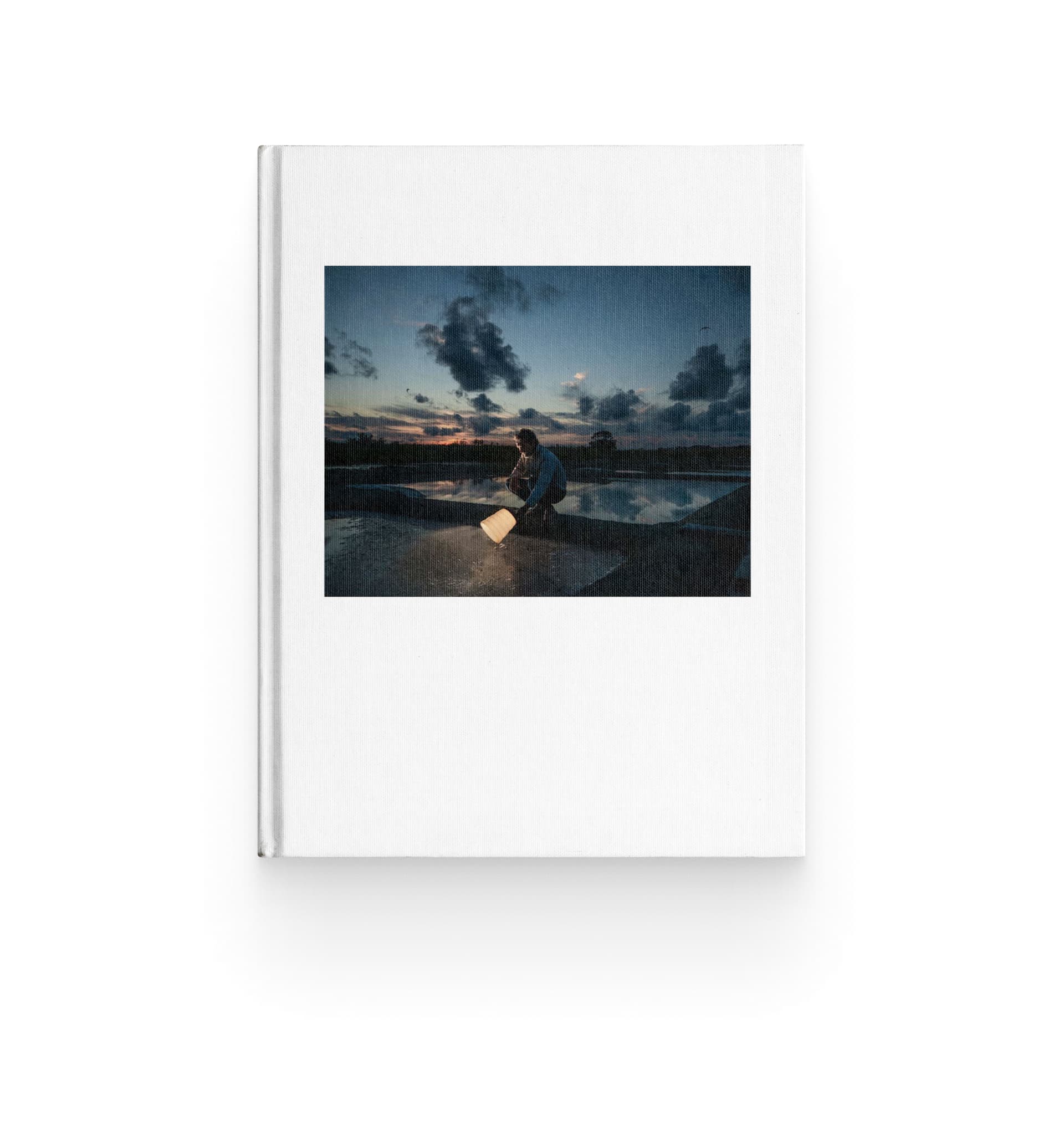

The event for the thirtieth anniversary of Orbital was also an opportunity to present the new creative project NOTTURNO LAVIANI with an exhibition at Foscarini Spazio Monforte. A photographic series in which Gianluca Vassallo interprets the lamps Laviani has designed for Foscarini in a storytelling that unfolds in fourteen episodes in which the lamps inhabit alien spaces.

What do you feel when you see the interpretation Gianluca Vassallo has made of your lamps?

The sensation is that of a circle coming to a close. Because Gianluca narrates his idea of light by using the objects I have designed as subtle but significant presences. Which is the same thing that happens when a person decides to put one of my lamps into their home. Looking at Notturno, then, I feel the same great emotion I feel when someone takes possession of one of my projects, or makes it a part of their existence: the sensation is that beautiful feeling of having done something that has meaning and relevance for others.

Which photo represents you best?

Definitely the one of Orbital outside: the yover with the torn circus poster. Because that’s what I’m like: everything and its opposite.

E-Book

30 Years of Orbital

— Foscarini Design stories

Creativity & Freedom

Download the exclusive e-book Foscarini Design stories — 30 years of Orbital and learn more about the collaboration between Foscarini and Laviani.

A fertile interchange, based on elective affinities, extending across three decades as a pathway of mutual growth.

Do you want to take a peek?